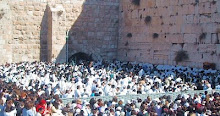

Celebrants at Anniversary MassReflections of Faith

A Necessary Mission: Three Decades of Theological Reflection[Woodstock Report, November 2005, No. 83]

Full texts of the remarks delivered at the anniversary Mass can be found here.

Corporate leaders come together to reflect on how their faith and business can and must interact. Lay parish leaders journey through a series of spiritual exercises aimed at helping them discern their calling as a community.

Doctoral students gather for an ecumenical seminar focusing on forgiveness in politics.

These are a few instances of theological reflection - reflecting the reach of the Woodstock Theological Center. The center's work began three decades ago, and in late September, several hundred people turned out for events marking this anniversary.

On September 25, approximately 200 Woodstock friends attended a 30th anniversary Mass celebrated principally by Cardinal Avery Dulles, S.J. A day later, Woodstock held a public forum on re-envisioning the papacy.

The events both celebrated and illustrated the ways of reflecting theologically upon urgent questions - and of bringing varied constituencies into this process of discernment.

Cardinal Avery Dulles, S.J.It's the Theology

"Woodstock is, in the first place, a theological center," Dulles said during his homily. "Its particular mission is to see what theology might have to say to people involved in secular callings such as business, law, medicine, and government."He added, "God's word is spoken, we believe, not only to the church but to the world."

During remarks at the end of the Mass, the cardinal was hailed by a Jesuit provincial as one of Woodstock's "founding fathers," but first among these was the late Pedro Arrupe, S.J.

Thirty-five years ago, the then-Superior General of the Society of Jesus declared, "In my judgment the first of all ministries that must be mentioned now is theological reflection on the human problems of today."

The beloved Arrupe issued his call in October 1970. He said on another occasion, "And by theological reflection I mean especially the need and urgency of an in-depth and exhaustive reflection on human problems, whose total solution cannot be reached without the intervention of theology and the light of faith."

Responding to the challenge, now-Cardinal Dulles began writing essays limning this notion of theological reflection. And two Jesuit provincials pursued their vision of a research center in Washington dedicating to promoting such in-depth reflection upon human problems. These latter "founding fathers," J. A. Panuska, S.J., of Maryland and the late Eamon Taylor, S.J., of New York, gave Woodstock its charge of seeking justice through the "intervention of theology."

"Woodstock is, in the first place, a theological center." - Avery Dulles, S.J.

"It is a mission which is as necessary today as it was" three decades ago, said Timothy Brown, S.J., Maryland provincial of the Society of Jesus, in his remarks about Woodstock's founding. "And it is a mission which has been pursued over the years not only by the Center's staff, but by hundreds and even thousands of people."

Timothy Brown, S.J.A Wider Circle of Reflection

The CEOs who gathered at an executive retreat center in Basking Ridge, New Jersey, were participating in this mission. The seminar in the summer of 2004 gave nearly two dozen high-level executives an opportunity to reflect on their experiences in the corporate world, in a relaxed and off-the record - as well as prayerful - atmosphere. Sponsored by Woodstock together with the Center for Catholic Studies and Institute on Work at Seton Hall University, the seminar drew extensively on Woodstock's approach to theological reflection and spiritual discernment. Woodstock has since held two similar events for executives at the Jesuit retreat center in Wernersville, Pennsylvania.The intimate groups of lay leaders that meet in places like Green Bay, Wisconsin, and Brooklyn, New York, have entered into this circle of reflection. They are drawing upon two companion books, Spiritual Exercises for Church Leaders, written by Woodstock senior fellow Dolores R. Leckey and freelance writer Paula Minaert. The books were produced by Woodstock through its Church Leadership Program, which Leckey coordinates, and are serving as a tool of discernment in parishes, dioceses, and other church settings.

The 15 doctoral students who came together in June of this year for an annual ecumenical seminar in Washington, D.C., were taking on this task of theological discernment. They were called together by the ecumenical Washington Theological Consortium, which devoted the discussion this year to the book, Forgiveness in International Politics: An Alternative Road to Peace, co-authored by three Woodstock fellows, William Bole, Robert Hennemeyer, and Drew Christiansen, S.J., and published last year by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Hennemeyer, a career U.S. diplomat who directed the Woodstock project that produced the book, spoke at the seminar held at Wesley Theological Seminary in Washington.

These are small-group snapshots of a deeper reflection process that began with the founding of Woodstock as a think tank in 1974. At the time, the center replaced a 103-year-old Jesuit seminary by that name, which closed in 1972. (Woodstock began observing its 30th anniversary during the past academic year; the late-September events marked the close of that celebration.)

During those early years, Woodstock's research projects led to such notable works as Claims in Conflict: Retrieving and Renewing the Catholic Human Rights Tradition, by David Hollenbach, S.J., and two widely read volumes edited by John C. Haughey, S.J., The Faith That Does Justice: Examining the Christian Sources for Social Change and Personal Values in Public Policy. Haughey returned as a senior research fellow last year.

In the 1980s and '90s, Woodstock began generating programs of ongoing outreach. Among them: Preaching the Just Word, which has introduced the concept of biblical justice to thousands of priest-homilists nationwide, and the Woodstock Business Conference, a national network of Catholic business people. Between 1990 and 1999, the center also ran four ongoing seminars in business ethics, bringing together ethicists and corporate leaders and leading to four Georgetown University Press publications touching on the ethical ramifications of corporate takeovers, managed healthcare, and other aspects of contemporary business.

In recent years, the center's projects have spawned works such as the Spiritual Exercises books, published by Paulist Press in 2003, and the forgiveness book, which won secondplace honors this year from the Catholic Press Association in the "pastoral" books category.

The Global Turn

An initiative that has struck a chord among Jesuits internationally is the Global Economy and Cultures project begun by Woodstock director Gasper F. Lo Biondo, S.J. The project, particularly its personal-narrative approach to studying interactions between economic globalization and local cultures, has influenced a global Jesuit task force preparing a report on the subject for Superior General Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, S.J. Lo Biondo belongs to that seven-member task force.The globalization project is an example of how Woodstock aims to think and act locally as well as globally. In his remarks during the anniversary Mass, Georgetown's vice president for public affairs and institutional advancement, Daniel R. Porterfield, testified to the impact on campus.

He recalled that, in September of last year, Father Lo Biondo arranged for 25 Jesuits from nearly as many countries to share a meal and conversation with approximately 90 students and a handful of faculty members. The Jesuits were in Washington for a consultation sponsored by the globalization project, which is co-directed by Lo Biondo and Rita M. Rodriguez, an international economist.

"This was a gift from God for us," said Porterfield. "We were able to put together a dinner workshop to allow students and faculty working on global justice issues to sit down and talk one-to-one with Jesuits who were living these exact questions."

He said the relationships formed during this encounter continued as some of the students went to study abroad and "reconnected with the Jesuits they had met in Washington, D.C."

Speaking of the globalization initiative, Porterfield added, "This project simply would not be done, anywhere, if not for Woodstock. We all would be diminished without this work."

Lo Biondo and Rodriguez are now working on a book related to the globalization project, and other books arising from other Woodstock projects are heading toward publication (see "In Focus" column).

Behind these and other theological ventures is a way of reflection, lashed to Ignatian spirituality, that is "continually open to new questions and perspectives," said Lo Biondo. "That's what we call conversion."

Full texts of the remarks delivered at the anniversary Mass can be found here.

News Opinions Religion

Guest Voices

Obituaries

Avery Dulles, 90; Prominent Catholic Cardinal, Theologian

| Avery Dulles was named to the College of Cardinals by Pope John Paul II. (By James A. Parcell -- The Washington Post) TOOLBOXCOMMENT Your browser's settings may be preventing you from commenting on and viewing comments about this item. See instructions for fixing the problem. Discussion Policy Comments that include profanity or personal attacks or other inappropriate comments or material will be removed from the site. Additionally, entries that are unsigned or contain "signatures" by someone other than the actual author will be removed. Finally, we will take steps to block users who violate any of our posting standards, terms of use or privacy policies or any other policies governing this site. Please review the full rules governing commentaries and discussions. You are fully responsible for the content that you post. |

Sunday, December 14, 2008; Page C08

Cardinal Avery Dulles, 90, a former professor at Catholic University who was born into a family of elite Protestant diplomats and became one of the country's most prominent Catholic theologians, died Dec. 12 at an infirmary at Fordham University in New York. Stricken with polio when young, he had post-polio syndrome, which led to progressive muscular and pulmonary deterioration.

Cardinal Dulles, who was appointed to the College of Cardinals by Pope John Paul II in 2001, was the first academic to be named to the Catholic Church's highest advisory council, as well as the first who had never served as a bishop.

Cardinal Dulles, a very tall and thin figure, was known for his unusual spiritual journey and came to be considered a calm statesman of Catholicism during a time of great turmoil.

Through more than 20 books and 800 articles, he articulated a conservative if tolerant case for Catholicism and the church's positions on contraception, sexuality, the role of women and clergy sex abuse. He served as a bridge between the Vatican and the more liberal American Catholic dissidents after the Second Vatican Council of the 1960s. In his later years, he was seen more as an advocate of orthodoxy and said church sanctions against priests charged in sex abuse scandals were too extreme.

He was the son of former secretary of state John Foster Dulles, who served under President Dwight D. Eisenhower. His uncle, Allen Dulles, was CIA director from 1953 to 1961.

Cardinal Dulles wrote and spoke often of his conversion to Catholicism, a faith still looked at skeptically by many Protestants in 1940, when he joined the church. Among the skeptics was his father, who was initially embarrassed about his son's religious path but later reconciled with him.

Avery Robert Dulles was born Aug. 24, 1918, in Auburn, N.Y., and grew up in a patrician Presbyterian family. His grandfather was a Presbyterian minister, and a great-grandfather and great-uncle had both served as secretaries of state.

Cardinal Dulles, who wrote about his spiritual journey in his autobiographical "A Testimonial to Grace" (1946), considered himself an agnostic when he entered Harvard College in the 1930s. He was drawn to Catholicism by his readings of the poet Dante Alighieri and the Catholic philosopher Saint Thomas Aquinas. The concept of objective moral standards appealed to him, but his spiritual quest was crystallized during a walk in Cambridge, Mass., when he looked at nature and began to see a governing purpose to the world.

"It was a matter of becoming aware of this reality behind everything that existed," he said in a 2001 interview in the New York Times Magazine. "That evening when I got back to my room, I think I prayed for the first time."

After graduating from Harvard in 1940, he served in the Navy during World War II and attended Harvard Law School for a few semesters before entering the Society of Jesus in 1946. He was ordained a Jesuit priest in 1956.

He received a doctorate in theology in 1960 from the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome and taught at Woodstock College, a now-closed seminary in Maryland, from 1960 to 1974. He was a theology professor at Catholic University from 1974 to 1988.

He wrote and lectured on many topics relating to Catholicism, with a specialty in ecclesiology, or the mission of the church in the world. Through his teaching and writing, Cardinal Dulles became "the United States' preeminent theologian," Washington Archbishop Donald Wuerl said in a statement.

Cardinal Dulles was at Catholic University when the Vatican disciplined many theologians who publicly disagreed with church authorities on a host of issues, including contraception, premarital sex, abortion, homosexuality and euthanasia. Cardinal Dulles sat on a faculty committee that defied the Vatican by recommending against the removal of a dissident theologian, but he did not speak out publicly against the church.

He said that he was opposed to the punishment of dissidents but that he could not support theologians and priests who routinely went against the church's teachings. His goal was to unify Catholics, he wrote, and to be a liaison between the Vatican and more free-thinking theologians.

After retiring from Catholic University, Cardinal Dulles joined the faculty at Fordham University, where he taught until last year. He served as president of the Catholic Theological Society of America and the American Theological Society in the 1970s and was also a member of the International Theological Commission, the U.S. Lutheran-Roman Catholic Dialogue and a consultant to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' Committee on Doctrine.

He had no immediate survivors.

Staff writer Matt Schudel contributed to this report.

More on washingtonpost.com

James Martin

Avery Dulles: Friend, Hero, Christian

Avery Cardinal Dulles's earthly life, which ended last week, was like something out of a Henry James novel. The scion of a fabled family--his father, John Foster Dulles, was Secretary of State under President Eisenhower--and educated at élite schools, he left his Presbyterian roots for the Roman church and, worse, the Jesuits. (Newsreels covered his 1956 ordination; the footage is now on Youtube.) During World War II, the young man joined the Navy, and won the French Croix de Guerre.

Dulles's conversion from agnosticism came during his undergraduate years at Harvard. As described in his autobiography, his turn to God was half in response to philosophical inquiry, half in response to noticing a tree in springtime, its little buds "in all innocence and meekness" following an unseen law that called to the student. His subsequent career as a Jesuit priest and theologian was, by all accounts, extraordinary. By the time of his death, he had written roughly 800 scholarly articles and 23 books; was considered the dean of American Catholic theologians; and was named a cardinal by Pope John Paul II--the only American Jesuit ever to receive that honor.

Over the last ten years of his life, I was fortunate to come to know a serious scholar who did not take himself too seriously. In October 2001, I was asked to accompany the great man to Boston, where he would receive one of his many awards, at a fundraising dinner. Before we boarded the train near Fordham University in New York, where Avery taught theology, I asked how he felt about the accolade. "I haven't really done anything to deserve it," he said. What about the books, the articles, the lectures? "I suppose," he said, "But I still feel awkward."

We arrived in Boston with barely enough time to dress in the Jesuit community where we were lodging. "Come by my room when you're ready," he said. An hour later, I knocked on his door. When he opened the door he was resplendent in his cardinal's black cassock with red piping, and the grand ferraiolo, or scarlet cape. At age 82, Cardinal Dulles couldn't reach the lowest buttons of his cassock so I knelt down to help. "How do I look?" he said with a sly smile. "As my mother would say," I told him, "you look very handsome." His patrician bearing was evident no matter what he wore; that night, the lanky Jesuit looked like Cardinal Abe Lincoln.

The next morning we caught the 8 a.m. train back to New York. (His Protestant work ethic, undimmed by his Catholicism, opted for the earliest train we could make.) Back at Fordham, a few Jesuits asked how things were in Boston; the country was still reeling from the Sept. 11 attacks. "People in Boston were upset that two of the planes that hit the World Trade Center came from Logan airport," I explained, relating what I heard the night before. Avery said, "How do you think I feel? One of them came from Dulles!"

That was one of the rare times he referred to that place, out of humility. Once, during a stay in Washington, D.C., a young Jesuit was assigned to drive Avery to the airport. He asked, "Which airport are we going to, Father? National or...?" Father Dulles said, "The other one!"

Given his lightheartedness, it seemed appropriate that, in 2001, during the Vatican ceremony when he was made a cardinal, Pope John Paul II placed the customary red biretta on Avery's head, and it toppled into the pope's lap. No one enjoyed telling that story more than the new cardinal. And he enjoyed recounting a tale from his Navy days, when as officer of the watch, he ordered his ship to fire on a German U-Boat in the Caribbean. When dawn came, Ensign Dulles realized that had bombarded a coral reef.

Avery was quietly generous to me, as to so many others. When I wrote about a topic I thought might prove controversial, Cardinal Dulles, in his late 80s, patiently read through a 400-page manuscript. He didn't have to tackle the whole thing, I explained, worried about the demands on his time. If he wanted, he could read only the part in question. "Of course I want to read the whole thing," he said. "How else will I understand it in its full context?" A few weeks later he sent a gracious note saying that all was in accord with "faith and morals." Later, in a phone call, he said the old teacher couldn't resist making a few minor corrections: Was I sure about the spelling of the name of St. Thomas Aquinas's mother? He signed off his calls with Naval precision: "Over and out!"

Avery was a model Jesuit. During a 2001 interview for America, he told me the he felt being a cardinal betokened a responsibility to accept more speaking engagements, even at his advanced age. The son of John Foster Dulles taught his friends what it means to be, in Jesuit lingo, a "man for others." Or, to use two old-fashioned words, what it means to be humble and kind. Or, in more common parlance, what it means to be a Christian.

James Martin, a Jesuit priest, is associate editor of America magazine and author of "My Life with the Saints."

Posted by James Martin on December 15, 2008 1:29 AM

| | ||||||

| ||||||

No comments:

Post a Comment