Filed under: College

May 22, 2006

Thank you very much. Thank you to Chairman Pat Stokes, the Chairman of the Board of Trustees, to Jack Connors, the vice chairman and, of course, a special thanks to Father Leahy and to Father Monan who have given the leadership of this great university that has made it a very, very special place.

It's wonderful to be back here in Boston and to join you for this splendid ceremony today. As an academic, I'm honored to be here at Boston College, a place of learning that is respected today not just in America, but throughout all the world. As a student of a Catholic high school, the Sisters of Loretta taught me, I am pleased to be at an institution of higher education with such strong and celebrated Catholic and Jesuit traditions.

But as a sports fan, I'm feeling a little uneasy standing right here on the 50-yard line of Eagles football. You see, I got my Master's Degree at Notre Dame. (Boos.) I acquired a passion for the fighting Irish. Now for decades, I have to admit, though, I've been on the other side of what has become known as "the holy war" between our Catholic colleges. And for decades I've watched in frustration as Boston College has consistently ruined some of Notre Dame's best seasons. (Applause.) Now I want to assure you I'm not here to wish the Eagles goodwill, but I do want to congratulate you on an impressive debut in the ACC last year and to say I know you'll do it again. (Applause.) Members of the Board of Trustees, faculty and staff, distinguished alumni and guests and especially graduates and students, family and friends, Class of 2006, thank you for welcoming me here. I will always remember my undergraduate commencement at the University of Denver. I remember how proud my parents were. I remember the thrill of achieving an important goal. What I don't remember is one word that my commencement speaker said. And chances are that you won't either and I promise not to take it personally.

Instead, all of you in the Class of 2006 will leave Boston College with other, more lasting memories. I bet most of you will remember Marathon Monday and a certain show called BC. I'm guessing most of you will remember late nights at Mary Ann's and parties at the Motts. (Applause.) Well, maybe you won't remember all of them. (Laughter.) And of course, I imagine that all of you will have no problem remembering that October night of your sophomore year when, after 86 years, the Boston Red Sox finally broke the Curse of the Bambino. (Applause.)

But of all your experiences at Boston College, none is more meaningful, of course, than the education you've received here. You see, education is transformational. It literally changes lives. That is why people work so hard to become educated and that is why education has always been the key to the American Dream, the force that erases arbitrary divisions of race and class and culture and unlocks every person's God-given potential. As John F. Kennedy once said, "All of us do not have equal talent, but all of us should have an equal opportunity to develop our talents."

The American vision of education inspired the founding of Boston College. For thousands of citizens facing discrimination and disadvantage, Boston College has been a sanctuary and a source of empowerment, a place where hardworking, capable people who just needed opportunity and someone who believed in them.

This college's mission resonates with me on a very personal level, for I've learned in my own life that education is the single greatest force for equality in the world. I first learned about the transformational power of education from stories about my paternal grandfather, a real family hero. You see, Granddaddy was a poor sharecropper's son from Ewtah — that's E-w-t-a-h — Alabama. And one day, Granddaddy decided he was going to get book learning so he asked, in the parlance of the day, where a colored man could go to school. And he was told that there was this little Presbyterian college just about 50 miles down the road.

So Granddaddy Rice saved up his cotton to pay for his first year's tuition and he went off to Stillman College. But after his first year, he didn't have any more money and they told him he was going to have to leave school. And Granddaddy said to a college administrator, "Well, how are those boys going to school?" And the administrator said, "Well, you see, they have what's called a scholarship. And if you wanted to be a Presbyterian minister, then you could have a scholarship, too." And Granddaddy Rice said, "You know, that's just what I had in mind," and my family has been college educated and Presbyterian ever since. (Laughter and applause.)

Because of all that my grandfather and others of my ancestors endured, including poverty and segregation, they understood that education was a privilege, but also that privilege confers obligations. And so today, I would like to suggest to you what I think are five important responsibilities of educated people.

The first responsibility is one that you have to yourself, the responsibility to find and follow your passion. I don't mean just any old thing that interests you, not just something that you could or might do, but that one unique calling that you can't do without. As an educated person, you have the opportunity to spend your life doing what you love and you should never forget that many do not enjoy such a rare privilege. As you work to find your passion, you should know that sometimes, your passion just finds you.

That's what happened to me. I was supposed to be a concert pianist. I could read music before I could read. And I started college as a music major. But around the end of my sophomore year, I started encountering prodigies, 12-year-olds who could play from sight what it had taken me all year to learn, and I thought, "I'm going to end up playing piano bar or teaching 13-year-olds to murder Beethoven or maybe playing at Nordstrom, but I'm not going to play Carnegie Hall." And I went to my parents and I decided that I had better find something else to do.

I was lost and confused, but one day, a wonderful thing happened. I wandered into a course on international politics taught by a Czech refugee who specialized in Soviet studies, a man who had a daughter by the name of Madeleine Albright. With that one class, I was hooked. I discovered tha t my passion was Russia and all things Russian. Needless to say, this was not exactly what young black girls from Birmingham were supposed to do in the early 1970s, but it just shows you that your passion may be hard to spot, so keep an open mind and keep searching.

The second responsibility of an educated person is the commitment to reason. Boston College has prepared you with a true education. You haven't been taught what to think, but rather, how to think, how to ask questions, how to reject assumptions, how to seek knowledge; in short, how to exercise reason. This experience will sustain you for the rest of your lives, but no one should assume that a life of reason is easy; to the contrary. It takes a great deal of courage and honesty. For the only way that you will grow intellectually is by examining your opinions, attacking your prejudices constantly and completely with the force of your reason.

This can be unsettling and it can be tempting instead to opt for the false comfort of a life without questions. Unfortunately, that's easier to do than ever. It's possible today to live in an eco-chamber that serves only to reinforce your own high opinion of yourself and what you think. That is a temptation that educated people have a responsibility to reject. There is nothing wrong with holding an opinion and holding it passionately. But at those times when you're absolutely sure that you are right, go find somebody who disagrees. Don't allow yourself the easy course of the constant "amen" to everything that you say. (Applause.)

A commitment to reason leads to your third responsibility as an educated person, which is the rejection of false pride. It is natural, especially among the educated, to want to credit your success to your own intelligence and hard work and good judgment. And it is true, of course, that all of you sitting here today are here because you do, in fact, possess these qualities, but it is also true that merit alone did not see you to this day.

There are many people in this country and in this world who are just as intelligent, just as hard working and just as deserving of success as you are. But for whatever reason, maybe a broken home, maybe poverty, maybe just bad luck, these people did not enjoy all of the opportunities that you have had at Boston College. Don't ever forget that. Never assume that your own sense of entitlement has gotten you what you have or that it will get you what you want. Boston College has summoned all of you to the Jesuit ideals of compassion and charity for those less fortunate. Now commencement marks your opportunity, indeed your obligation, to graduate with wisdom and humility. (Applause.)

The fourth responsibility of the educated person is to be optimistic. Too often, cynicism can be the fellow traveler of learning and I understand why. History is full of much cruelty and suffering and darkness and it can be hard sometimes to believe that a brighter future is indeed dawning. But for all of our past failings, for all of our current problems, more people now enjoy lives of hope and opportunity than ever before in all of human history. This progress has been the concerted effort not of cynics but of visionaries and optimists, of impatient patriots who dealt with our world as it was, but who never ever accepted that they were powerless to change that world for the better.

Here in America our own ideals of freedom and equality have been borne through generations by optimists, by people of reason, to be sure, but just as importantly, by people of faith, people who reject the all-too-common assumption that if you can't see something happening and measure it, then it can't possibly be real.

There was a time when the goal of democracy in America seemed impossible, but because people had faith in democracy's promise, today, it seems that it must have always been inevitable. There was also a day in my own lifetime when the hope of liberty and justice for all seemed impossible. But because individuals kept faith with the ideal of America, it seems that it was always inevitable that today, there has been a decade since we last had a white male Secretary of State. (Applause.)

You have been fortunate to study at a college where reason and faith exist together and reinforce one another. But you're headed into a world where optimists are too often told to keep their ideals to themselves. It is your responsibility as educated people to remain optimistic no matter what, but that's not all. You have an obligation to act on those ideals and this, I believe, is the final responsibility to the educated person; really, the most important responsibility of all, to work to advance human progress.

What do I mean by human progress? I believe that all human beings share certain fundamental aspirations. They want protections for their lives and their liberties. They want to think freely and to worship as they wish. They want opportunities to educate their children, boys and girls, and they want to be ruled by the consent of the governed, not by the coercion of the state. So I would define human progress this way. Progress is humankind's ability to view more and more of our differences, whether of race or religion or culture or gender, not as a license to kill or a cause for repression, but as matters of no moral significance whatsoever.

All too often, difference has been used to divide and to dehumanize. I grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, the Birmingham of Bull Connor and the Ku Klux Klan, a place that was once quite properly described as the most segregated city in America. I know how it feels to hold aspirations when half your neighbors think that you're incapable or uninterested in anything higher. In my professional life, I've listened with disbelief as it was said that men and women in Asia and Africa and Latin America and Russia and in the Middle East today did not share the basic aspirations of all human beings. Somehow, it was thought, these people were just different and by that, it was meant unworthy, unworthy of what we enjoy.

It is your responsibility as educated people to reject these prejudices and to help close the gaps of justice and opportunity that still divide our nation and our world. I know this mission is very close to the heart of Boston College. The Jesuit ideal of service to others has inspired this class to devote thousands of hours of your own time to help those in need. Most of you have spent a summer break on mission service or worked here at home in impoverished American communities, perhaps in New Orleans after the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Others ventured beyond our shores to assist the needy in countries like Brazil and Jamaica and Mexico.

This experience, I imagine, has taught you that progress never unfolds passively or inevitably. No, the promise of human progress is always carried forward by men and women who serve a cause greater than themselves. I know how hard it can be these days, when we see images of genocide in Darfur or violence in Iraq or destruction along our own Gulf coast, to believe that such a thing of human progress is possible is sometimes difficult. I know that even optimists among us sometimes feel tested today, but in moments like these draw solace from education and also from historical perspective.

I spent last summer reading the biographies of America's Founding Fathers. I read of Jefferson and Adams and Washington and Hamilton. And when you read of their lives and their times, you are struck by the overwhelming sense that there is no earthly reason that the United States of America should ever have come into being. But not only did we come into being, we endured. And not only have we endured, we have thrived. We have thrived despite the fact that when the Founding Fathers said, "We, the people," they didn't mean me. We have thrived despite the fact that my ancestors were deemed to be three-fifths of a man and sold at auction. We have thrived despite the fact that it was only in my lifetime that we finally guaranteed the right to vote for all Americans. So remember, even when the horizon seems shrouded in darkness, the hope of a brighter beginning is always in sight.

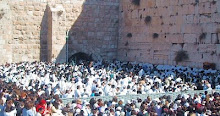

I've been told that in keeping with the senior tradition, all of you gathered this morning on the roof the Beacon Street garage to watch the sunrise on your last day as college students (applause) — your first day as men and women of the world. This morning indeed marks a new and glorious beginning for all of you and all of you are well-prepared for what lies ahead. You now leave Boston College to join the ranks of the world's most privileged community, the community of the educated. So as you leave, let me ask you to bear a few things in mind. Remember your responsibilities to find your passion, to use your reason, to cultivate humility, to remain optimistic and always to serve others. Remember this moment right now and remember all of those who contributed so that it could come — your parents and your families and your friends who supported you through all of these times.

But remember this, too. You've had a wonderful opportunity to become educated people, but what really matters is not what you have learned and not what is said to you on this day, but what you do with all the days ahead of you. May God speed you on your way. Thank you.

No comments:

Post a Comment